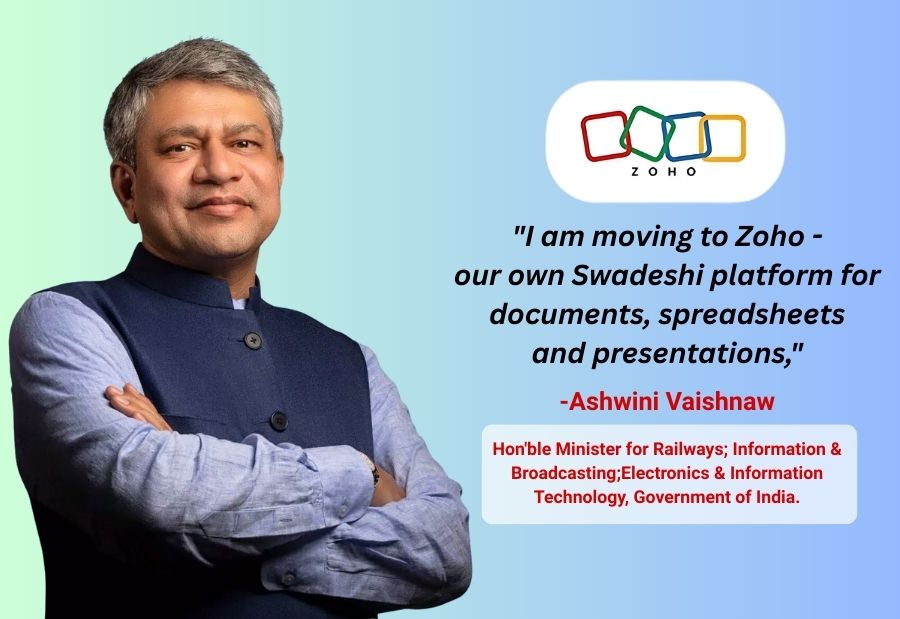

When India’s IT Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw publicly announced that he was switching from Google Docs and Microsoft Office to Zoho — a homegrown productivity suite — it stirred quiet applause within India’s startup ecosystem and caught the attention of the global tech community.

On the surface, it seems like a personal preference. In context, it is a deliberate signal of intent, one that aligns with India’s broader push for digital self-reliance and strategic autonomy in its tech stack.

“We will make our nation proud,” responded Zoho founder Sridhar Vembu on X, thanking the minister for what he called a “huge morale boost” for engineers who have worked for decades building the product suite.

A Swadeshi Signal with Strategic Intent

India has never lacked talent or innovation in software. What it has often lacked is institutional trust in homegrown products. This endorsement subtly challenges that bias.

It reflects a larger shift. India’s Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA) underscores growing concerns over data sovereignty. The India Stack is being cited globally as a model for public digital infrastructure. Government initiatives such as Make in India, Atmanirbhar Bharat, and Startup India are not just policy slogans; they are reshaping how we think about indigenous technology.

Seen through this lens, Vaishnaw’s move is more than a personal tech switch. It is a calibrated nudge toward policy-aligned digital consumption.

Zoho: Not Just Indian, but International-Grade

Sridhar Vembu’s Zoho is not a startup waiting for validation. It is a global player.

With more than 130 million users in over 150 countries, and a portfolio of more than 55 business applications, Zoho competes head-on with Microsoft 365, Google Workspace, Salesforce, QuickBooks, and others. It is bootstrapped, independently run, and headquartered in rural Tamil Nadu.

This matters. When a Cabinet Minister chooses Zoho for official work, it is a recognition not just of its Indian origin, but of its product maturity. For the Indian software ecosystem, this is more than validation. It is proof that excellence can come from within.

Rethinking the Default

For decades, global software companies have been the default choice for Indian institutions, from ministries to municipal corporations, from banks to public schools.

Vaishnaw’s decision challenges that norm. It opens up a set of critical questions:

- Will Indian ministries now explore alternatives built in India?

- Could Indian SaaS platforms gain meaningful entry into public procurement?

- Will this signal lead to incentives, pilot programs, or policy adjustments favoring indigenous software?

For Microsoft, Google, and others, this may be seen as a symbolic loss. But for Indian SaaS players, it is an opportunity that rarely comes with such visibility.

What Needs to Be Proven

Public praise is useful, but public sector adoption depends on reliability, security, and scale. Government departments require software that is:

- Scalable across large institutions

- Compliant with data governance and security norms

- Integrated with legacy systems and workflows

- Supported by enterprise-grade service and uptime guarantees

The shift toward swadeshi software must be earned not just through patriotism, but through performance.

Context and Timing Matter

This moment arrives at a time when it is rapidly reimagining its digital architecture.

- UPI has reshaped global conversations around payments.

- ONDC is attempting to rewire digital commerce.

- Bhashini is building AI tools in Indian languages.

- DigiLocker, CoWIN, and Aarogya Setu have demonstrated the power of scalable public tech platforms.

But enterprise and productivity software remains an area dominated by international firms. It is yet to invest fully in building sovereign software layers for institutions and enterprises.

That is the gap Zoho occupies — and potentially bridges.

Changing the Narrative

Vaishnaw’s endorsement may not immediately cause ministries to cancel existing software deals. But it shifts the conversation about what is acceptable, trusted, and viable.

It opens space for serious consideration of whether India should:

- Prioritize Indian software in public sector IT stacks

- Build sovereign digital infrastructure, not just adopt open APIs

- Encourage vendor diversity to avoid strategic lock-in

This is not about isolating from global tech. It is about expanding choices and removing the unspoken bias that foreign means better.

In Conclusion

Ashwini Vaishnaw’s decision to adopt Zoho may be framed as a symbolic move, but it represents something deeper. It reaffirms that India has both the talent and the infrastructure to build world-class software, and it encourages institutions to reconsider what they choose to adopt. For Indian SaaS companies, this is more than visibility. It is validation.

The question now is whether Indian software will rise to meet this opportunity — and whether the public and private sectors will give it a fair chance to do so.

Also read: Viksit Workforce for a Viksit Bharat

Do Follow: The Mainstream formerly known as CIO News LinkedIn Account | The Mainstream formerly known as CIO News Facebook | The Mainstream formerly known as CIO News Youtube | The Mainstream formerly known as CIO News Twitter |The Mainstream formerly known as CIO News Whatsapp Channel | The Mainstream formerly known as CIO News Instagram

About us:

The Mainstream formerly known as CIO News is a premier platform dedicated to delivering latest news, updates, and insights from the tech industry. With its strong foundation of intellectual property and thought leadership, the platform is well-positioned to stay ahead of the curve and lead conversations about how technology shapes our world. From its early days as CIO News to its rebranding as The Mainstream on November 28, 2024, it has been expanding its global reach, targeting key markets in the Middle East & Africa, ASEAN, the USA, and the UK. The Mainstream is a vision to put technology at the center of every conversation, inspiring professionals and organizations to embrace the future of tech.